About The Nature Of Code

Foreword

The Nature of Code is a site, a book and a Youtube channel (part of 'The Coding Train') by Daniel Schiffman. Its stated aim is to teach how to simulate natural systems with Javascript and more particular wih the p5.js library, which in its turn is based on the Processing language

So what is the link with Basic256?

Well apart that they are both programming languages, there is not a lot of overlap... Basic256 is a nice QT-based IDE but still on top of a relatie primitive programming language variant of Basic ('Beginners All Symbolic Instruction Code'). It is an interpreted language, has no OOP (Object Oriented Programming) capabilities, vectors and related subroutines etc. However they are both programming languages so we should be able to emulate some of the simpler programs in The Nature of Code.

I will try to keep to the same structure as the original book/ebook/site.

I would suggest you follow the first 'episodes' of the Nature of Code Youtube series and if you like what you see, I would advise to buy the book as using it to look up things later on is a lot easier than going through a bunch of Youtube vides...

Randomness and Perlin Noise

Randomness

Now, Basic256 already comes with a nice random function rand. This function generates (psuedo-)random numbers between 0 and 1. Consequent numbers however bear no relation to each other. Again, I would refer to the original site for deeper detail

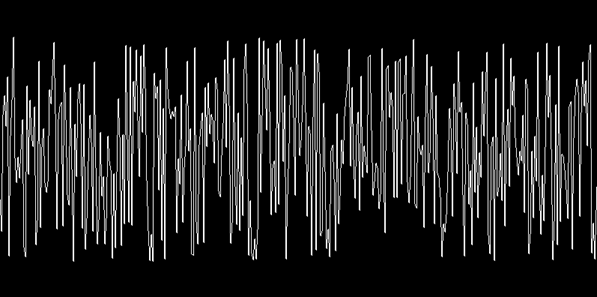

Plotting a 1D graph of consecutive random numbers gives what best can be called static or white noise. (a 2D graph would look like 'snow' on old TV sets).

You can see the 1D result of plotting random numbers by running the following code where we draw a line from one generated number to the next(0-1 sized to screen):

Fastgraphics

width=1000

height=400

graphsize width,height

color black

rect(0,0,width-1,height-1)

oldx=0

oldy= height/2

#Draw

while 1

for x = 1 to width-1 step 2

color black

rect (x,0,x+4,height-1)

y= rand*300-150+height/2

color white

line(oldx,oldy,x,y)

oldx=x

oldy=y

next x

if x >= width then x=0

refresh

pause 0.08

end while

Feel free to change the stepsize, the random number sizing or the pause (to give nice results depending on your computer - Raspberry Pi or Ryzen 7...) . Try to work in 2D... Experimenting is fun!)

Random Noise

Perlin noise

What is Perlin Noise? Well, according to Wikipedia, Perlin noise is a type of 'gradient noise' developed by Ken Perlin in 1982. It has many uses, including but not limited to: procedurally generating terrain, applying pseudo-random changes to a variable, and assisting in the creation of image textures.

To be fair, in the beginning the actual math behind it didn't mean a lot to me. The best explanation for me would be the one from Daniel Schiffman himself in the Coding Train episode about Perlin Noise. The easiest explanation start around minute 7.

That was the original idea behind the method I used for a Perlin Noise experiment that I coded around 2012-2013 for my BTK2 Demo program "Perlin Mountains"

Now, unfortunately there is no built-in Perlin Noise function in Basic256, which means one has to write ones own, so that's what I and my good friend ChatGPT did. This cooperation (hey, I did write the prompt!) resulted in 2 Basic256 functions Perlin1D(t) and SinglePerlin(t). The single biggest advantage is that you can generate a continious range of Perlin Noise and are not limited (as I was) to Perlin Noise in a given range

The simple Perlin Noise algorithm can be used by everyone, but the follow-up Simplex Noise algorithm (also by Ken Perlin) was granted a patent. Simplex Noise has fewer directional artifacts, works in higher dimensions and has a lower computational overhead. Kurt Spencer then developed OpenSimplex Noise to overcome the patent-related issues. Still other noise generators exist like Fractal Noise and Worley (Voronoi) Noise. Here, we'll use the simple Perlin Noise algorithm

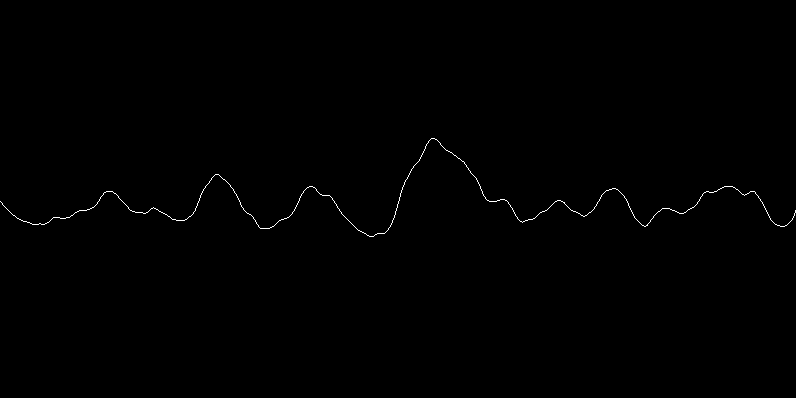

Single Perlin Noise 'range'

Marching Perlin Noise

The image and the video start of with the same 'range' since in both programs, the seed is set to the same fixed value

Random and Perlin Noise 'Walkers'

We can extend both random and Perlin noise into the 2D plane by creating a 'Walker', an object (ie a circle) that has an initial position px,py to which we add a velocity (speed) sx and sy. The values for both sx and for sy would either be random noise values or Perlin noise values (upscaled a bit since both provide values between 0 and 1)

As one would expect the Random noise Walker would move pretty 'jittery' while the Perlin noise Walker would seem to move in a more fluid way. The RandomNoise Walker moves faster due to the additional overhead of calculating Pelin Noise values

You can see the difference by running both programs:

Fully random motion

Perlin Noise motion

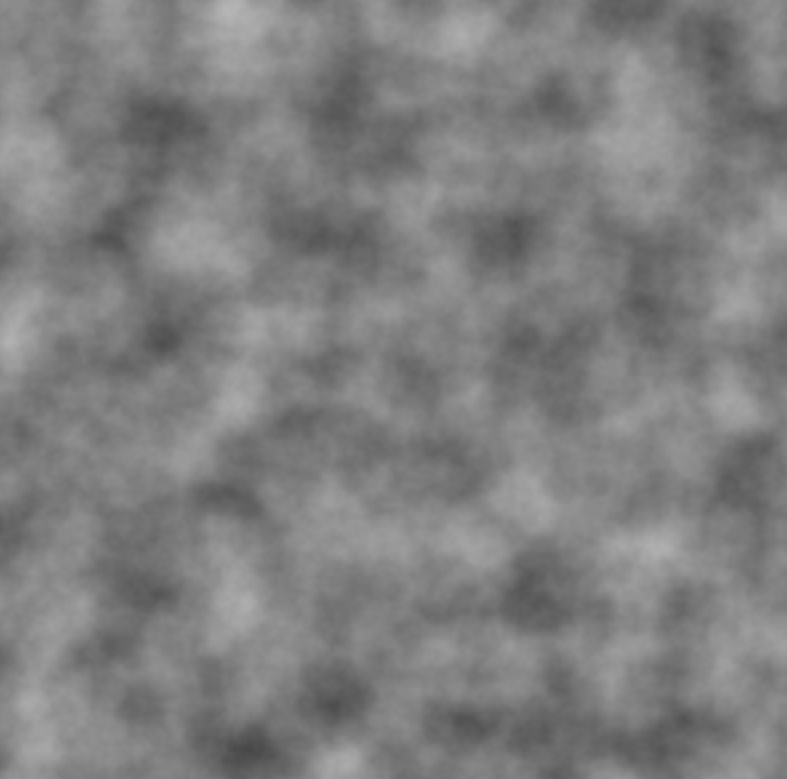

2D Perlin Noise Clouds'

While the 'Walker' objects are simply points moving over a 2D plane, Perlin Noise really comes into its own when using it for procedural textures.

For 2D Perlin Noise however, we need another set of functions, here called Perlin2D, SinglePerlin2D and some helper functions (Thanks ChatGPT) With these, we get a single Perlin Noise value for each (x,y) point in the plane.

We then tranform the Perlin2D value (still between 0 and 1) into a color value by multiplying it by 255. Unfortunately, as these functions are not built in and so have to be executed in slow interpreted Basic, all these calculations take quite a bit of time...

Perlin Noise texture

After a couple of seconds we then get the following result:

Moving balls (was 'Vectors' but Basic256 lacks vectors and vector math)

Bouncing Ball

An object can be considered to have a position, a speed and eventually an acceleration. This acceleration is the sum of all forces working on the object. Now the Nature of Code book gives a nice explanation via Newtons laws on these elements and I strongly recommend you to read these

The Nature of Code book however extensively uses vectors and vector math which are part and parcel of p5.js but don't exist in Basic256. While in Basic256 we can of course use simple variables for position and speed and acceleration like:

pos_x=100

pos_y=100

speed_x=1

speed_y=1

acc_x=0.05

acc_y=0.005

Instead, I opted to use arrays as these look a bit like vectors...

pos={100,100} In p5.js, this would be pos = createVector(100,100)

speed = {1,1} In p5.js, this would be speed = createVector(100,100)

acc = {0.05,0.005} In p5.js, this would be acc = createVector(0.05,0.005)

For our first simulation, we will use a bouncing ball (well, circle actually) with fixed position and speed and constrained to the plane (bouncing of the sides). There is no accceleration and no forces working on it so it's like a 'perpetuum mobile' that will run forever

Bouncing Ball

And this is what it looks like:

Acceleration - Constant (same direction), Random (any direction) and euh, directional (aiming at a target)

An object in motion can accelerate in a given direction, meaning at every time step its speed increases a set amount while the direction might change (but does not have to).

Our first example will be an object falling with no change in direction. In order to see the acceleration, we give it a trail and when it 'falls' off the bottom of the screen, it will reappear at the top. So, just the position will change, not the speed or acceleration

Constant Acceleration

And this is what it looks like:

Our first acceleration example had a velocity change in only one direction, namely down (y-direction). This made changing the velocity simply adding the y-component of the acceleration 'vector' (array) to the y-component of the position 'vector (again, array) in a loop.

The Nature of Code's Vector chapter, when talking about acceleration talks a lot about p5.js vectors. Like one can create a random2D vector, which returns a 'normalized' vector, ie a vector with lenght 1. Again I would suggest you turn to the source material for more info.

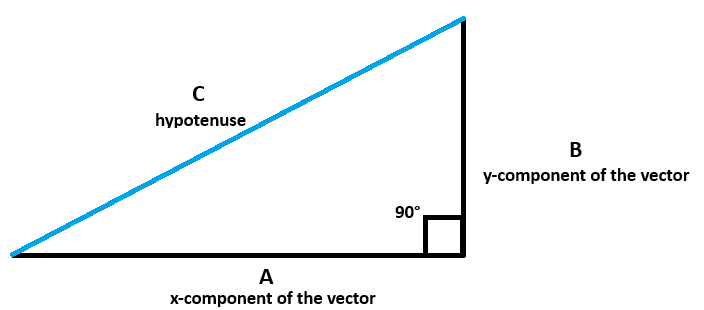

Our pos, speed and acc arrays each have two elements. So what is the vector? Well, think back to equilateral triangles from school:

You probably remember that C²=A²+B² so, C = sqr(A²+B²). C is the 'vector', showing the size/magnitude of the step. In a 'normalized' vector, C always has size 1, so to get a 'normalized' array (vector!) in Basic256, we need to calculate C and then divide the x and y component by that C.

A Basic256 function can only return a single value, so I wrote 2 functions Normalize_a and Normalize_b. I can also do it by a single function mag(a,b) to calculate C itself and then divide the a and b by c. Drawback here is that one has to first store the vector values in scalars and then pass these to the function mag(x,y) wich returns C

Of course, in our example, the normalized vector is between -1 and 1. If we just used two random values between -1 and 1 using rand*2-1 we would get a non-normalized vector between 0 and sqr(2) (or 1.41421...) so the result would not really be visible here. However, if the x and y values are large (let's say >100), the normalized vector would give you the direction it points in, as we will see later

So a program moving and changing the ball's acceleration randomly could like this:

Random Acceleration

And this is what it looks like:

Our last acceleration example will have the object accelerate towards a moving target, namely the mouse!

So, we know the position of the object (its x and y values) and we know the position of the of the mouse (detected with mouseX and mouseY). We now subtract the object's position from the mouse's position. This gives us our equilateral triangle with the vector pointing from the object's position to the mouse but with the 'magnitude' of the vector set to the exact distance to the mouse. We do not want this or the object will have its velocity explode.

We now 'normalize' the vector so that is still points to the mouse but with a 'length' of 1. This becomes our acceleration. However, even if we add this acceleration of 1 to the velocity of the object, the velocity will grow much too fast, so we have to cap the velocity to a maximum speed of let's say 10. We could make the vector smaller but after a while the velocity would again get too large.

The object will never 'catch' the mouse but will always overshoot due to the velocity being to great for the acceleration to overcome. Best outcome is a sort of circular or ellipsoid orbiting of the mouse.

You can of course play with the acceleration setting or the velocity capping to see what happens.

Acceleration to Mouse

And this is what it looks like:

It does look nicer on a larger plane than the 400x400 of the video...

Forces

Gravity and wind

A simple ball bouncing and influenced by wind and gravity forces. Wind strength is determined by the location of the mouse: If the mouse is in the middle of the plane then there is no wind, at the left side the wind strength is -2.5, at the right side it is +2.5

Note that there is no negative force so the ball bounces back to the same height, leadin again to a 'perpetuum mobile'

Also, here we have just a single ball. That makes it possible to use separate arrays for position, velocity and acceleration. Even with 2 balls, you could go the same way. But multiple balls at once will require a different approach.

Bouncing Ball with gravity and wind

And this is what it looks like:

Multiple Balls with gravity and wind

When using multiple balls, like 3 in this example, in p5.js, one would make a Ball class and instantiate it three times. As Basic256 is not OOP, we cannot do that.

Also, having three different objects also allows us to use different masses for each object. Different masses react differently to a wind force but, as Galileo showed, mass does not affect gravity so heavy objects fall as fast as light objects

To get around the OOP limitation, for the three objects, we can use a single large array to store the data on all three objects.

dim obj[3,7]

# This creates an array of max of 3 objects, each with 7 properties:

# 0 = pos_X

# 1 = pos_Y

# 2 = vel_X

# 3 = vel_Y

# 4 = acc_X

# 5 = acc_Y

# 6 = mass

This makes the code a bit harder to read as you'd have to know that obj[2,4] is the acceleration along the x-axis of the third object.

Note that there is no loss of velocity on the bounce so the bounces go just as high as the previous ones.

Forces on multiple objects

And this is what it looks like (half way into the clip, I click a few times with the mouse to affect the objects with a wind force):

Friction as a damping force

Up till now, we had a kinda idealistic environment where energy never dissipated, so bouncing objects kept bouncing forever. Now, let's try to create a dissipating force and like in the NoC book/Site, let's take friction

Again everything is clearly explained in the book so I'll skip the physics. Suffice to say that whenever two surfaces come into contact, they experience friction. This friction causes the kinetic energy of an object to be converted into another form (eg heat), giving the impression of loss, or dissipation.

Friction of course widely differs from substrate to substrate (eg ice versus sandpaper). The strength of the friction is called the 'Coëfficient of friction'. You can find loads of such Coëfficients on the web. We'll be using the arbitrarily value of 0.5

Then, there is also the Normal force, a force perpendicular (90°) to the surface the object is touching. This force is important when you have a slope in the surface (going downhill) but for our simulation, we will simply set it to 1. The real magnitude of friction is the formula 'Coëff of friction times the Normal'

Friction force occurs only when our object touches the ground. It's direction is inverse to the velocity, so we will create friction as the reverse of velocity, normalise the resulting vector and multiply it with the Friction Coëfficient. We then simply apply this force to the velocity, just as we did with wind and gravity

The wind easily moves the objects according to their mass while in the air, but once the objects come to a standstill, you can see the impact of friction as now friction comes into play at each timestep and not just at the bounce

Friction on three objects

And this is what it looks like:

(the objects do not bounce in syncronization becauses the bigger mass touches the floor sooner, thus starts its bounce sooner)

Friction on masses of objects

In the previous example, we had three objects that we declare in a predefined array of lenght 3. That gave us 21 rows of data. What is we want 10, 20, 100 objects?

Well, we just create our array iteratively based on the desired number of objects! For more visual diversity, I also added an additional parameter so that every object has its own coëfficient of friction (between 0.5 and 1.5)!

nr_obj=20

dim obj[nr_obj,8]

# create max 10 objects with 7 properties:

# 0 = pos_X

# 1 = pos_Y

# 2 = vel_X

# 3 = vel_Y

# 4 = acc_X

# 5 = acc_Y

# 6 = mass

# 7 = coëfficient of friction

# object parms

for i = 0 to nr_obj-1

obj[i,0] = width/(rand * 4)

obj[i,1] = (height)/(rand * 15)

obj[i,2] = 0

obj[i,3] = 0

obj[i,4] = 0

obj[i,5] = 0

obj[i,6] = rand * 100 +50

obj[i,7] = rand+0.5

next i

Friction on masses of objects

And this is what it looks like:

Air and Fluid resistance

Friction also occurs when a body passes through a gas or a liquid (think of a parachute jump or a dive in water). These are forces somethimes called drag and like all the other forces, we can also implement them in our little universe

You can (and should) read all the detail of this under the Forces/Modeling a force/Air and liquid resistance section of the site/book.

While the formula for drag is a bit more complex than for friction, we will again simplify this for our environment so that the drag force is the speed squared times the drag coëfficient times the opposite direction (which is the velocitiy's unit vector but negative) or F = v² * c * velocity unit vector * -1. Simple....

Here, we use a single object so for readability sake, we use separate arrays for position, velocity and acceleration

I can't stress enough that the content of the site/book is a lot more in depth than what I describe here in 4 lines...

adding drag to an object

And this is what it looks like:

Drag on multiple objects

Again, when using multiple objects (3+) it is better to create each of the objects in a loop and store them in a single array. Having multiple objects lets us show the difference in friction between objects of a different mass.

You can clearly see that, unlike with gravity, friction force DOES depend on the mass of an abject, just like wind does and heavier objects are less impacted by friction so move faster through the medium.

Of course, this is still quite an idealized universe. In real life, things like the surface size also impacts the friction. (a thin ,long object falling pointy end first will be less impacted by friction that the same object with the same mass falling sideways...)

drag on multiple objects

And this is what it looks like:

Gravitational attraction - single orbiting body

Probably the most famous force (in physics!) we are aware of is gravity. While the apple is 'pulled' to the ground by the earth's attraction, the earth also has a force pulling it towards the apple. The difference between the two however is so large that this is practically zero

Two object of more or less the same mass do exert a detectable gravitational force on each other. The formula of this gravitational force is G*m1*m2/r² where G is the Gravitational constant. (In our simplyfied universe, we will just set this to 1), m1 and m2 are the masses of the two objects and r² is the square of the distance. the direction of this force is the unit vector of the distance

In other words, the gravitational force between two bodies is proportional to the mass of those bodies and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them.

Let's start with a large immovable mass of value 3 (but drawn larger) in the center and a smaller mass of value 2 that is attracted to that central mass. Since we have only a single moving object, to make it easier on the eyes, we will give it its own arrays for pos, vel and acc

Gravitational attraction

And this is what it looks like:

Gravitational attraction - two bodies orbiting

Instead of having a single body orbiting a stationary one, we will now simulate the gravitational pull where two bodies rotate around each other.

With just 2 bodies, we can still afford to give each their own positional, velocity and acceleration vectors, as well as their mass and the force they feel toward each other

Two bodies with the same mass (here very small) and opposite (small) velocities will form a nice dance around a fixed point in space.

The moment just the masses differ or just the speeds vectors differ, thing still work as designed, but the system will move out of the visual plane quite rapidely

Try to mix things up a bit like making one a bit larger or a lot larger, change the speed vectors slightly etc

Gravitational attraction - 2 bodies

And this is what it looks like: